In previous posts, I addressed the relationship between sexual difficulties and such powerful negative emotions as guilt, shame, and rage. I briefly addressed the emotion of grief in this article, but I also wanted to take the opportunity to expand on the ways in which grief affects sexual functioning, particularly because it is such a prevalent experience for so many people.

When we experience grief, inevitably we are dealing with some kind of a loss. Grief is the emotional response to loss. Typically, we may think of the loss of a loved one, but loss doesn’t just have to be about the death of a person– it could be about the death of an idea, a hope, a dream, an identity, and so on. In many ways, grief is a normative process in human development. We’ve all had to (or will have to) grieve the loss of childhood dreams and opportunities; we have to accept that we will never be an astronaut or professional ball player. And we also have to grieve the natural effects of the aging process– we cannot stay young and keep our looks and health forever. So grief is an inevitable experience for all of us in one way or another. We cannot escape it. But there is also a large gap between this kind of normative grief and the unresolved, perhaps pathological, grief that causes long-term difficulties.

When grief becomes unresolved it is typically because an individual is stricken with grief but does not allow him or herself to fully experience it. Essentially, the person is afraid to experience the grief, and develops something resembling a phobic response to the possibility of ever having to experience it at some point in the future. The ramifications of this deep-seated fear of grief can manifest in pervasive long-term difficulties for the individual, particularly in the area of forming and maintaining relationships.

If an earlier formative relationship that was painful or did not end well is not fully grieved, it often feels difficult to form healthier and happier relationships in the future. This is because, paradoxically, forming a new, healthy relationship threatens to provoke a fresh round of grief because it is a stark contrast and harsh reminder of what was painfully wrong in the earlier relationship. In other words, newfound happiness often provokes grief because it forces us to face what had been missing all along. It is only by facing this grief head-on do we allow ourselves to finally bury the past and make new, fresh choices moving forward.

Let’s take a look at a few specific examples. For most people, their earliest relationship experiences in life are with their parents, or with some other kind of caregiver. These early relationship experiences are so crucial that they form the foundation of how we view and interpret all future relationships in life. It is almost like a wheel of fortune, in that it is pure luck whether our early relationship experiences are felt as warm, safe and nurturing, or as chaotic, confusing and dangerous. And this pure luck depends on the well-being and emotional stability of these early relational figures. In other words, we have no control over the nature of these early relationships, even though we may often end up feeling guilty and responsible in hindsight. As children, we don’t have the ability to change our environment or to even have a realistic, multi-dimensional understanding of the situation. The child experiences the pain and hopelessness of a less than ideal relationship but has no idea what to do about it except to blame itself.

And herein lies the heart of the matter: if it is our human nature to bear the brunt of the responsibility for the pain of early relationships, it is also in our human nature to (even if irrationally and/or unconsciously) believe that, if given a second chance, we could make things right. So, a typical example of this scenario is when an individual takes on a partner that is reminiscent of his or her mother/father– the same personality traits, the same behavior, and so on. On some unconscious level the person feels that, if only this new partner could be straightened out, it would make right all of the wrongs of the past. In this way, the individual never has to grieve that the first relationship is dead and buried, never to be revived again. Instead, it feels alive, like it is happening in real time all over again. And so, the old relationship never needs to be buried– it lives on in perpetuity through each successive relationship. Freud called this the “repetition compulsion.”

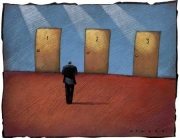

Another scenario is that instead of repeating the same relationship themes over and over, the individual just shuns all relationships at all for fear of reviving old pangs of grief. If the individual never gets close to another person, he or she never has to experience the same old hurts of disappointment, rejection, and inevitable abandonment. But, by doing so, this individual never gives him or herself the chance to heal these old wounds through new, corrective emotional experiences. Nothing wagered, nothing earned. So, in this case, protecting oneself from pain only serves to reinforce it.

For those with old relational trauma, grief is a very painful and formative emotion that must eventually be faced in order to pave the way for new relational experiences. Those with unresolved grief may either shun all close intimate relationships entirely or find themselves on a continuous hamster wheel of identically themed relationships that all resemble each other. As a therapist, it is my role sometimes to gently help people gradually face the painful emotions that they have been avoiding for years, so that they can finally master them instead of being in their control.

Prevention: Is Sex Addiction Real?

Prevention: Is Sex Addiction Real? Romper: Emotional Infidelity

Romper: Emotional Infidelity Fatherly: BDSM More Common Than You Think

Fatherly: BDSM More Common Than You Think E! Online: Marrying a Murderer

E! Online: Marrying a Murderer Who Magazine: What is Bisexuality?

Who Magazine: What is Bisexuality? CNN: Why Men May Exaggerate Their Sex Numbers

CNN: Why Men May Exaggerate Their Sex Numbers Women’s Health: 10 Kinky Sex Ideas

Women’s Health: 10 Kinky Sex Ideas NY Post: How Tattoos Can Sabotage Your Love Life

NY Post: How Tattoos Can Sabotage Your Love Life Allure: 8 BDSM Sex Tips to Try If You’re a Total Beginner

Allure: 8 BDSM Sex Tips to Try If You’re a Total Beginner

Great article in Prevention Magazine about the sex addiction controversy. Check out what I had to say.

Great article in Prevention Magazine about the sex addiction controversy. Check out what I had to say.

Romper approached me again for another quote, this time about emotional infidelity.

Romper approached me again for another quote, this time about emotional infidelity.

Interesting piece in Fatherly about BDSM in which I was interviewed.

https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/bdsm-kinky-sex-not-uncommon/

Interesting piece in Fatherly about BDSM in which I was interviewed.

https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/bdsm-kinky-sex-not-uncommon/ E! News picked up my an interview I did with Vice a few years ago about hybristophilia, which is the attraction to criminals. Very interesting story.

E! News picked up my an interview I did with Vice a few years ago about hybristophilia, which is the attraction to criminals. Very interesting story.

Who is Australia's version of People Magazine. They wanted to know what bisexuality is and I provided some insight.

Who is Australia's version of People Magazine. They wanted to know what bisexuality is and I provided some insight.

Seems like something doesn't add up on sex surveys-- are men exaggerating their number of partners? Check out what I tell CNN.

Seems like something doesn't add up on sex surveys-- are men exaggerating their number of partners? Check out what I tell CNN.

Women's Health asked me for some kinky ideas to spice up one's sex life.

Women's Health asked me for some kinky ideas to spice up one's sex life.

I was interviewed by the NY Post about all the ways in which I've seen bad tattoos sabotage relationships.

I was interviewed by the NY Post about all the ways in which I've seen bad tattoos sabotage relationships.

Allure Magazine asked me about tips for BDSM beginners.

Allure Magazine asked me about tips for BDSM beginners.

I answer questions from Salon.com about the infamous porn site PornHub.

I answer questions from Salon.com about the infamous porn site PornHub.

I tell Cosmo about the personality traits of monogamous individuals.

I tell Cosmo about the personality traits of monogamous individuals.

I explain to Refinery29 why it's so important to not fake orgasms in a relationship.

I explain to Refinery29 why it's so important to not fake orgasms in a relationship.

I am interviewed in this fairly nuanced piece on the pros and cons of porn.

I am interviewed in this fairly nuanced piece on the pros and cons of porn.

I am interviewed by Headspace, one of the best meditation and mindfulness apps available, on how to become more present.

https://www.headspace.com/blog/2017/05/26/enjoy-sex-more/

I am interviewed by Headspace, one of the best meditation and mindfulness apps available, on how to become more present.

https://www.headspace.com/blog/2017/05/26/enjoy-sex-more/ I am interviewed in this intriguing Business Insider article on how often happy couples have sex.

I am interviewed in this intriguing Business Insider article on how often happy couples have sex.

The Huffington Post in South Africa profiles my work around challenging sex addiction (including my red/yellow/green menu exercise) .

The Huffington Post in South Africa profiles my work around challenging sex addiction (including my red/yellow/green menu exercise) .

I go deep into the sex toy business with Vice.

I go deep into the sex toy business with Vice.

I give some insight into this interesting topic.

https://thetab.com/us/2017/03/22/happens-boyfriend-leaves-another-man-63306

I give some insight into this interesting topic.

https://thetab.com/us/2017/03/22/happens-boyfriend-leaves-another-man-63306 I am featured in this outstanding article in UK's Independent on women and virtual reality porn. I thought this was a fairly sharp and nuanced piece.

I am featured in this outstanding article in UK's Independent on women and virtual reality porn. I thought this was a fairly sharp and nuanced piece.

I give Redbook some pointers on having a 3some for the first time.

I give Redbook some pointers on having a 3some for the first time.

Playboy sent a journalist to watch Fifty Shades Darker, and then compared the movie with the results from my recent groundbreaking research on BDSM. Great article, enjoy!

Playboy sent a journalist to watch Fifty Shades Darker, and then compared the movie with the results from my recent groundbreaking research on BDSM. Great article, enjoy!

I am featured in this terrific New York Magazine article, discussing some of the finer points brought up in the earlier article in SELF magazine (see listing below).

I am featured in this terrific New York Magazine article, discussing some of the finer points brought up in the earlier article in SELF magazine (see listing below).

I am featured in this terrific article in SELF magazine on the nuances of the sex addiction debate.

I am featured in this terrific article in SELF magazine on the nuances of the sex addiction debate.

Complex asked me to weigh in on this provocative topic.

Complex asked me to weigh in on this provocative topic.

I weigh in in this great advice column in Thrillist by Elle Stanger.

I weigh in in this great advice column in Thrillist by Elle Stanger.

Great episode, check it out.

https://soundcloud.com/futureofsex/04-exploring-sexual-fluidity-bicuriousity-for-women-featuring-skirt-club-and-dr-michael-aaron

Great episode, check it out.

https://soundcloud.com/futureofsex/04-exploring-sexual-fluidity-bicuriousity-for-women-featuring-skirt-club-and-dr-michael-aaron I give couples advice on how to deal with differences in preferred sleeping arrangements.

I give couples advice on how to deal with differences in preferred sleeping arrangements.

Alternet does a great job of reviewing my book. Check out the link below.

Alternet does a great job of reviewing my book. Check out the link below.

In this episode, we talk about the societal myths of sexuality, including:

In this episode, we talk about the societal myths of sexuality, including:

I was asked to appear on Australian radio. It was a very fun segment, will post the link when I have it!

I was asked to appear on Australian radio. It was a very fun segment, will post the link when I have it! I appear on the Stereo-Typed podcast to discuss my new book, fantasies, and our shadow self. Click the audio player below and enjoy!

https://www.spreaker.com/user/crazyheart/stereo-typed-8-dancing-with-your-shadow

I appear on the Stereo-Typed podcast to discuss my new book, fantasies, and our shadow self. Click the audio player below and enjoy!

https://www.spreaker.com/user/crazyheart/stereo-typed-8-dancing-with-your-shadow I appear on the Boom Doctors Podcast to discuss my new book Modern Sexuality and my work as a sex therapist. Clink the link below to listen in.

http://theboomdoctors.com/2016/09/21/ep-132-michael-aaron-on-his-work-as-a-sex-therapist-his-new-book-modern-sexuality/

I appear on the Boom Doctors Podcast to discuss my new book Modern Sexuality and my work as a sex therapist. Clink the link below to listen in.

http://theboomdoctors.com/2016/09/21/ep-132-michael-aaron-on-his-work-as-a-sex-therapist-his-new-book-modern-sexuality/ I was asked by Nylon Magazine to weigh in on the subject of porn and what it means about the individual consumer. Pretty good non-pathologizing piece, check it out here:

I was asked by Nylon Magazine to weigh in on the subject of porn and what it means about the individual consumer. Pretty good non-pathologizing piece, check it out here:

I was interviewed by Vocativ about a new virtual reality series entitled "Virtual Sexology," designed to provide breathing and relaxation exercises in a virtual reality format to help individuals improve sexual functioning. Will something like this prove effective? The jury is out, but check out what I had to say...

I was interviewed by Vocativ about a new virtual reality series entitled "Virtual Sexology," designed to provide breathing and relaxation exercises in a virtual reality format to help individuals improve sexual functioning. Will something like this prove effective? The jury is out, but check out what I had to say...

I appeared on the nationally broadcasted Fusion Network Hotline show to discuss the GOP platform of porn as a "public health crisis." As part of the discussion I debate Dr. Neil Malamuth on porn and sexual violence. I thought this was a very thorough and productive half hour, which you can watch below:

I appeared on the nationally broadcasted Fusion Network Hotline show to discuss the GOP platform of porn as a "public health crisis." As part of the discussion I debate Dr. Neil Malamuth on porn and sexual violence. I thought this was a very thorough and productive half hour, which you can watch below:

In this Huffington Post article, I advise couples to use sex menus to spice things up. Check out all the details in the link below.

In this Huffington Post article, I advise couples to use sex menus to spice things up. Check out all the details in the link below.

I appeared on French national tv channel Canal + on the Emission Antoine tv show, discussing the psychology behind financial domination. I will post a video clip of the interview shortly.

I appeared on French national tv channel Canal + on the Emission Antoine tv show, discussing the psychology behind financial domination. I will post a video clip of the interview shortly. I was interviewed on Huffington Post's Love + Sex Podcast, which I'm told is the most downloaded sex and relationship podcast on iTunes. In this episode, I dispel the wild myths about "sex roulette" parties.

I was interviewed on Huffington Post's Love + Sex Podcast, which I'm told is the most downloaded sex and relationship podcast on iTunes. In this episode, I dispel the wild myths about "sex roulette" parties.

I was interviewed for an upcoming online sexuality discussion series, the Sexual Reawakening Summit. It features many top sex therapists from around the country and you can access it by using this link:

I was interviewed for an upcoming online sexuality discussion series, the Sexual Reawakening Summit. It features many top sex therapists from around the country and you can access it by using this link:  In the April edition of my Men's Fitness 'Sex Files' Q&A column, I answer questions about anal sex and porn. Hurry and pick up a copy before it's off the stands!

In the April edition of my Men's Fitness 'Sex Files' Q&A column, I answer questions about anal sex and porn. Hurry and pick up a copy before it's off the stands!

I was asked by Women's Health Magazine to provide some advise on how to incorporate some new positions to spice up one's sex life. With a bunch of pictures and diagrams, I'm sure you'll find something that will intrigue you.

I was asked by Women's Health Magazine to provide some advise on how to incorporate some new positions to spice up one's sex life. With a bunch of pictures and diagrams, I'm sure you'll find something that will intrigue you.

Looks like Yahoo News picked up the Reuters article on women's fears that their partners expect sexual perfectionism. Check it out.

Looks like Yahoo News picked up the Reuters article on women's fears that their partners expect sexual perfectionism. Check it out.

My latest interview with Reuters, this time about social pressure on women to be perfect sexually. "Our society is filled with sexual myths and misconceptions, mostly stemming from a combination of our culture's puritanical roots, as well as rampant consumerism, which feeds off individual insecurities to sell unnecessary products," Aaron said.

My latest interview with Reuters, this time about social pressure on women to be perfect sexually. "Our society is filled with sexual myths and misconceptions, mostly stemming from a combination of our culture's puritanical roots, as well as rampant consumerism, which feeds off individual insecurities to sell unnecessary products," Aaron said.

Head out to the newsstands and grab a copy of the Jan 2016 issue of Men's Fitness Magazine to see the premier of the new monthly "Sex Files" column in which I answer readers' sex questions. In this month's issue I answer a question in which a guy is looking to help his girlfriend enjoy more pleasure when she is having sex on top. Check out the screenshot below to see my response:

Head out to the newsstands and grab a copy of the Jan 2016 issue of Men's Fitness Magazine to see the premier of the new monthly "Sex Files" column in which I answer readers' sex questions. In this month's issue I answer a question in which a guy is looking to help his girlfriend enjoy more pleasure when she is having sex on top. Check out the screenshot below to see my response:

Love& is a new magazine about relationships and sex. They interviewed me about common things that women may want their guys to improve upon in the bedroom. One of the big ones is touch, as a lot of men are way too rough and don't know how to adjust their touch to what their partner wants. For more on this, and other pointers, check out the article itself below:

Love& is a new magazine about relationships and sex. They interviewed me about common things that women may want their guys to improve upon in the bedroom. One of the big ones is touch, as a lot of men are way too rough and don't know how to adjust their touch to what their partner wants. For more on this, and other pointers, check out the article itself below:

Market analysts predict that new virtual reality technology will revolutionize the way we experience media, and will specifically boost the porn industry to unprecedented levels. This detailed article covers a lot of ground, addressing both the technology, business and social ramifications of virtual reality porn. I was asked to give my take on the issue and somehow a 20 minute phone conversation was distilled to a brief paragraph at the end of the piece, but nonetheless, it is still a worthwhile read.

Market analysts predict that new virtual reality technology will revolutionize the way we experience media, and will specifically boost the porn industry to unprecedented levels. This detailed article covers a lot of ground, addressing both the technology, business and social ramifications of virtual reality porn. I was asked to give my take on the issue and somehow a 20 minute phone conversation was distilled to a brief paragraph at the end of the piece, but nonetheless, it is still a worthwhile read.

Does Bill Cosby have a fetish for unconscious women? Who knows? He's not a client and I've never met him, so I cannot say for sure, but this provocative piece in the NY Times tries to get to the bottom of his alleged bizarre behavior. The reporter did a great job dealing with some uncomfortable material, so be sure to click the link below to see what I had to say on this issue:

Does Bill Cosby have a fetish for unconscious women? Who knows? He's not a client and I've never met him, so I cannot say for sure, but this provocative piece in the NY Times tries to get to the bottom of his alleged bizarre behavior. The reporter did a great job dealing with some uncomfortable material, so be sure to click the link below to see what I had to say on this issue:

I was recently asked by a reporter from Men's Fitness magazine to discuss reasons why a heterosexual man might refrain from having sex with a willing woman. The questions were basically soft balls, seemingly aimed at a younger, more inexperienced, male audience, but hey, I managed to drop a few decent pointers, relating to finding out if the woman is in a relationship, and if so, what kind of relationship she is in before diving in. If you want to take a look and poke around more, you can go directly to the article below. You are going to have to click to page 3 to see my quotes, btw.

I was recently asked by a reporter from Men's Fitness magazine to discuss reasons why a heterosexual man might refrain from having sex with a willing woman. The questions were basically soft balls, seemingly aimed at a younger, more inexperienced, male audience, but hey, I managed to drop a few decent pointers, relating to finding out if the woman is in a relationship, and if so, what kind of relationship she is in before diving in. If you want to take a look and poke around more, you can go directly to the article below. You are going to have to click to page 3 to see my quotes, btw.

I was recently interviewed for a Men's Health article on sex toys designed for men. They wanted to know my take on these "robotic masturbators" (as they called them) and as always, I tried to take a fair and balanced view of things. I pointed out that they could be used as a way to get better acquainted with one's sexuality (as well as get some much needed relief), but an over-reliance on technology may also limit guys from developing the necessary skills that would help them form romantic relationships.

At any rate, hurry on over to the article here--

I was recently interviewed for a Men's Health article on sex toys designed for men. They wanted to know my take on these "robotic masturbators" (as they called them) and as always, I tried to take a fair and balanced view of things. I pointed out that they could be used as a way to get better acquainted with one's sexuality (as well as get some much needed relief), but an over-reliance on technology may also limit guys from developing the necessary skills that would help them form romantic relationships.

At any rate, hurry on over to the article here--  Go check out a great, and I mean GREAT, absolutely fascinating article in the May issue of Upscale Magazine, entitled "Secret Lovers," in which I am interviewed regarding the hush hush world of the swinger subculture. The writer does a really good job of trying to understand the psychology of folks who practice consensual non-monogamy and I think the piece is very even-handed, with some practical tips for couples who are curious about dipping their toes in the lifestyle. I'll leave you with a quote from one of the swingers profiled in the piece, which I think gives a good feel for the tone and depth of the article-- "I love to see her with two guys and two girls at once. I enjoy submissive women, and there is no sexier submission than to watch my wife please me by pleasing others." If that sounds interesting, then I suggest you head out and grab a copy. It's well worth the read.

Go check out a great, and I mean GREAT, absolutely fascinating article in the May issue of Upscale Magazine, entitled "Secret Lovers," in which I am interviewed regarding the hush hush world of the swinger subculture. The writer does a really good job of trying to understand the psychology of folks who practice consensual non-monogamy and I think the piece is very even-handed, with some practical tips for couples who are curious about dipping their toes in the lifestyle. I'll leave you with a quote from one of the swingers profiled in the piece, which I think gives a good feel for the tone and depth of the article-- "I love to see her with two guys and two girls at once. I enjoy submissive women, and there is no sexier submission than to watch my wife please me by pleasing others." If that sounds interesting, then I suggest you head out and grab a copy. It's well worth the read. I am featured in the Sex Q&A section of Cosmo's April 2014 issue, in which I get asked about BJs, Plan B, sex in hot tubs, and all kinds of other tittilating reader questions. They did a good job of adding all kinds of humor, including a silly picture of tea bags-- need I say more? It's a can't- miss hoot. Go and check it out at news stands now!

I am featured in the Sex Q&A section of Cosmo's April 2014 issue, in which I get asked about BJs, Plan B, sex in hot tubs, and all kinds of other tittilating reader questions. They did a good job of adding all kinds of humor, including a silly picture of tea bags-- need I say more? It's a can't- miss hoot. Go and check it out at news stands now! I just recently did an interview for a cool podcast called

I just recently did an interview for a cool podcast called

i lost my wife 8 year ago, the love of my life, she died very quickly, i had two heart attacks and open heart urgery so i never thought my wife would die before me. I am 73 now and have not had any relationships with a woman, i have had lots of opportunity to be with a woman, but i just cant seem to give myself permission to live and go on with my life. I watch gran kids and throw all my emotion into loving them, but i know something is missing, i think of my wife a lot, Mary was special, and as odd as it seems i cant let go of what i know is gone. Is it possible that this is causing me to be impotent,,,and why do i feel guilty to have sex with a woman, i am afraid i am not able to have a relationship ,,,,,,